Class Asteroidea — The Sea Stars

|

Living echinoderms have a 5-fold radial symmetry (occasionally secondarily bilateral). They have calcite plates in their skin (dermis) providing a skeleton of varying rigidity depending on how loose or fused the plates are. Sea stars, such as this Hystrigaster horridus, are probably the most recognizable echinoderms.

Hunsrück Slate, Germany

Early Devonian Period

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

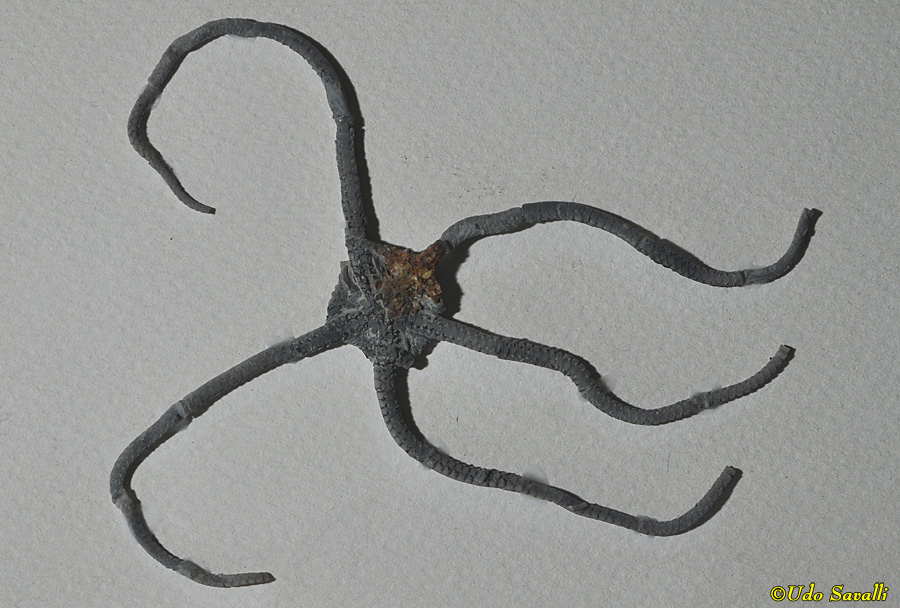

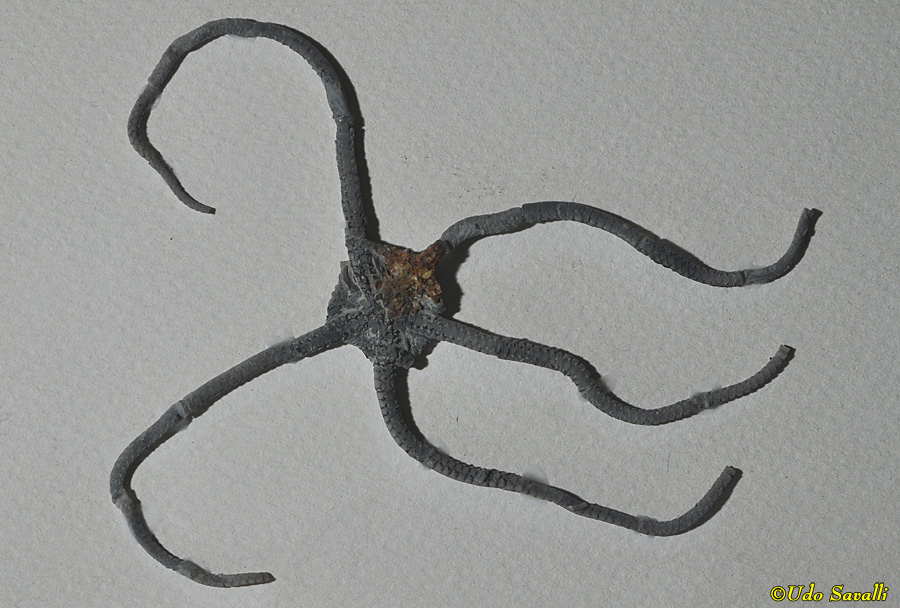

Class Ophiuroidea — The Brittlestars

|

Brittlestars differ from sea stars in having a smaller, more distinct central disk and longer, more flexible arms. This example is Ophiura graysonensis.

Del Rio Formation, McLennan Co., TX

late Cretaceous, Cenomanian Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Onychaster flexilis brittlestar.

Edwardsville Formation, Crawfordsville, Montgomery Co., IL

Early Mississippian, Osagean Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Ophiomusium gagnebini death assemblage.

Effinger layers, Solothurn Switzerland

Late Jurassic, Oxfordian Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

Echinoidea — Sea Urchins & Sand Dollars

|

Sea Urchins can be thought of as a sea star with its arms folded above it until they touch, then the arms are flattened out and joined into a sphere and their plates fused together into a solid skeleton (technically called a test). Like with sea stars, the mouth is on the underside (right image). Note that this Dendraster gibbsii sand dollar is not truly radially symmetric, with the center of the radial pattern offset from its true middle.

Kettleman Hills, CA

Pliocene Epoch

personal collection

|

|

|

Class Crinoidea — Sea Lilies

|

Today the crinoids (sea lilies) are relatively uncommon and largely restricted to fairly deep ocean water, but they have a much more extensive fossil history. Crinoids have a cup-shaped body surrounded by numerous branched or spiny arms (the mouth in the center of the cup faces up). the arms are used to filter tiny food particles from sea water. Most crinoids are supported on a long stalk that attaches to the sea bottom. Upon death, the parts of the skeleton usually separate, leaving stem segments as very common fossils, sometimes forming a dense "strew"

Frankfort, Kentucky

Ordovician Period

in situ

|

|

|

|

This fairly typical crinoid, Actinocrinites gibsoni, is remarkably complete, with a body (called the calyx) on the left, rings of arms surround a central mouth (which would face up in life). The complete stalk is present with some anchoring roots as well.

Edwardsville Formation, Montgomery Co., Indiana

Carboniferous Period, Early Mississippian Epoch, Osagean Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Arthroacantha punctobrachiata crinoids.

Ontario, Canada

Devonian Period

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Crinoids can grow in dense beds, making them important components of prehistoric reefs. Such beds can produce death assemblages, such as this one of the species Jimbacrinus bostocki.

Australia

Early Permian Period

Museum of Ancient Life, Utah

|

|

|

|

Crinoids can also often be found in mixed species assemblages, indicating a diverse crinoid reef with many species, as here.

Wyoming Dinosaur Center

|

|

|

|

Crinoid mixed species assemblage.

Crawford, Indiana

Carboniferous Period, Late Mississippian Epoch; 322 Ma

New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, Albuquerque

|

|

|

|

Mixed crinoid plate with: Ulrichicrinus coryphaeus (center), Cyathocrinites iowensis, C. multibrachiatus, S. harrodi, Sarocrinus granilineus, & Macrocrinus mundulus (several).

Edwardsville Formation, Montgomery Co., Indiana

Carboniferous Period, Early Mississippian Epoch, Osagean Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Mixed crinoid plate with: Macrocrinus mundulus, Scytalocrinus sp., Agaricocrinus splendens, Barycrinus sp., Sarocrinus nitidus, Platycrinus brevinodus, & Onychocrinus ulrichi.

Edwardsville Formation, Montgomery Co., Indiana

Carboniferous Period, Early Mississippian Epoch, Osagean Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Mixed crinoid plate, left to right: Gilbertsocrinus dispanus, Parisocrinus crawfordsvillensis, & Actinocrinites gibsoni

Edwardsville Formation, Montgomery Co., Indiana

Carboniferous Period, Early Mississippian Epoch, Osagean Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

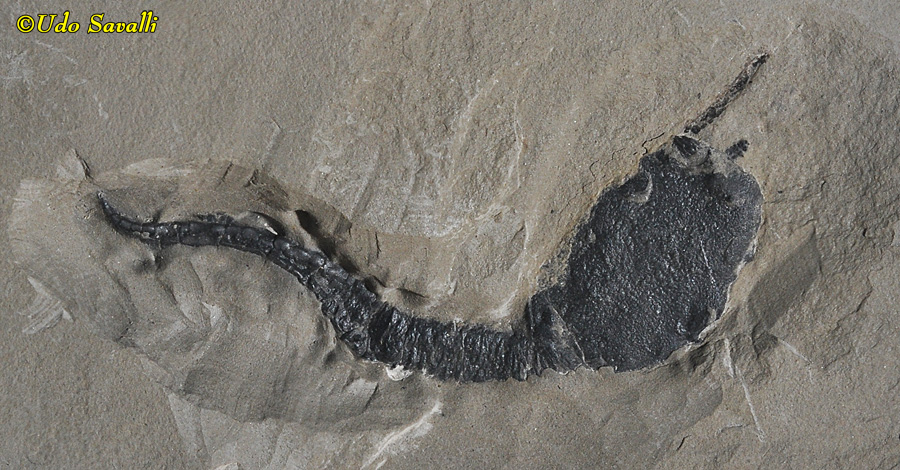

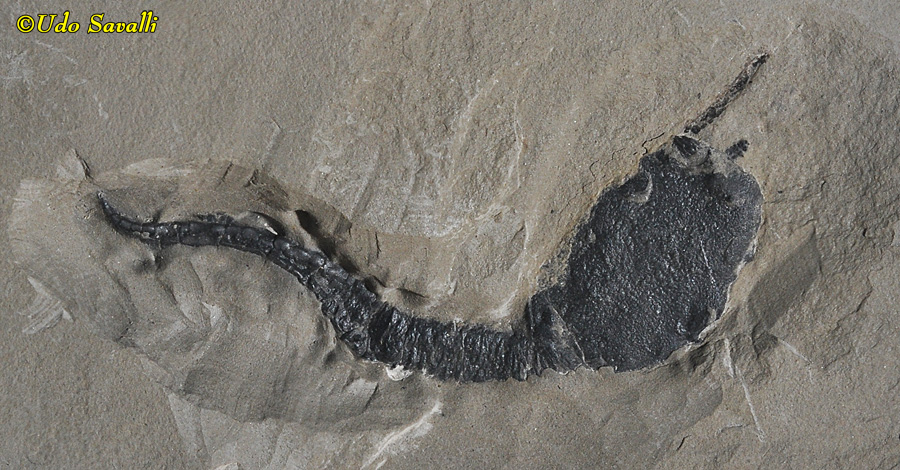

Some crinoids, such as this Agaricocrinus splendens, have been found with brittlestars such as this Onychaster sp. living in their arms (the brittlestar arms are coiled compared to the straight crinoid arms). It is not clear if this relationship was parasitic or mutually beneficial.

Edwardsville Formation, Montgomery Co., Indiana

Carboniferous Period, Early Mississippian Epoch, Osagean Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

An association between the crinoid Actinocrinites gibsoni and the brittlestar Onychaster sp. (darker than the crinoid).

Edwardsville Formation, Montgomery Co., Indiana

Carboniferous Period, Early Mississippian Epoch, Osagean Stage

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Not all crinoids have stalks. For example, Uintacrinus socialis lacked a stalk but had very long arms; it probably floated above the sea bed.

Mancos Shale, Mesa Co., CO

Late Cretaceous Period, 85 Ma

Denver Museum of Science & Nature

|

|

|

|

The "roaming crinoids," Seirocrinus subangularis, were giant crinoids that attached to floating logs and other debris. This specimen is about 9 m long but they could get up to 20 m.

Posidonia Formation, Holzmaden Shale, Germany

Late Jurassic Period, 145 Ma

Wyoming Dinosaur Center

|

|

|

|

Crinoid reef with mixed species.

Carboniferous Period, Early Mississippian Epoch; Iowa

Museum of Ancient Life, Utah

|

|

|

|

Silurian crinoid reef, with Siphonocrinus nobilis (red) and other unidentified species (note also gastropod snails and brachiopods).

Middle Silurian Period, 425 Ma; Wisconsin

Denver Museum of Science & Nature

|

|

|

|

Silurian crinoid reef diorama

Middle Silurian Period, 425 Ma; Wisconsin

Denver Museum of Science & Nature

|

|

|

Extinct Classes of Echinoderms

|

Echinoderms evolved from a bilaterally symmetric ancestor (divisible into right and left halves) before becomming radially symmetric, and the most primitive extinct echinoderms still have this bilateral symmetry. One such example is Pleurocystites squamosus (Class Cystoidea).

Ontario, Canada

Ordovician Period

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Carpoids (Class Homoiostelea) have long puzzled scientists for their mix of unusual characteristics. They have a skeleton composed of plates typical of echinoderms, and some were stalked, but they lacked some internal features (such as a water-vascular system) and were either biltaterally symmetric or asymmetric. This species, Castericystis vali, has a single arm (top right) in addition to its larger stalk (on the left) (the small structure protruding from the center of the main body is likely an anal tube).

Marjum Shale, Millard Co, Utah

Middle Cambrian Period, 520 Ma

Denver Museum of Science & Nature

|

|

|

|

The Class Edrioasteroidea is comprised of flattened animals with 5 curved "arms" that radiated from the center and sat fixed upon the disk-shaped body (due to the differing curvatures of the arms, they were not truly radially symmetric). They grew on hard surfaces, including shells such as brachiopods and were probably filter feeders (using tiny soft-tissue structures called tube feet). This species is Isorophus laevis.

Ontario, Canada

Ordovician Period

Black Hills Institute Museum, South Dakota

|

|

|

|

Although the Class Eocrinoidea resembles the true crinoids in overall shape, there are a number of structural differences that indicate these are a more primitive type of echinoderm. This is Gogia spiralis.

Wheeler Shale, Delta, Utah

Middle Cambrian Period, 507 Ma

Museum of Ancient Life, Utah

|

|

|

|